When it comes to flying electric aircraft, it seems the one thing that gives people the most trepidation is programming their electronic speed control. Fear that a mistake will ruin the motor, speed control or LiPo pack (or all three!) is common. Rest easy, pilots: the chances of that happening are very remote. Most of the time a mistake in programming will result in loss of efficiency, poor performance, or something far less than catastrophic. Even better is the fact we’ll give you pointers to avoid all of those possibilities and more in the next few paragraphs!

THE SAME, BUT DIFFERENT

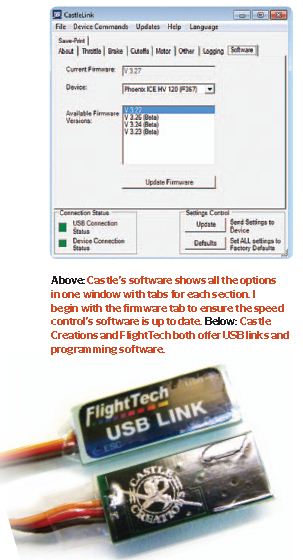

All brands of speed controls do the same thing: control the motor. They all do it with very similar techniques, but how you program them can vary slightly. Every speed control I’ve used has employed some method of programming with a sequence of moving throttle sticks on the transmitter and responding to various tones. This is great because you can always adjust at the field without the need of a computer, but it’s also the most confusing method. I view it as a last resort, but a valuable one. Most brands now offer either USB interfaces that allow you to program speed controls by connecting them to a computer and using their proprietary software. There are also programming cards available from most of the big name manufacturers that allow programming by simply plugging the card into the speed control, no computer is necessary. That is the ultimate for field adjustments.

SPEED CONTROL TERMINOLOGY

Most manufacturers use the same vocabulary to describe the functions of their controllers. It’s important to have a minimal understanding of these terms.

Brake setting. Most controllers will let you decide if you want a brake set or not. The brake can be set to “on” if you want your prop to stop when you reduce your throttle to idle/off. This is mostly used for folding props, but some folks like to stop their prop for better glide with the motor off, even if it’s not a folding type. There are settings for soft brake, hard brake and no brake. The default for most manufacturers is no brake or soft brake, but once again, read the instructions. Some Jeti controllers (hobby-lobby. com) default to full brake. If you’re flying a helicopter, you’ll want to be sure the brake is set to “off.”

Low-voltage cutoff. This feature ensures you don’t damage your LiPo pack by drawing the voltage too low during a flight. The default on most controllers is “auto” and most of the time that is just fine. Various brands use different methods to determine that, but the standard is somewhere around 70 to 75% of the voltage level detected when first armed. This is important because if you fly more than one flight on a pack without recharging between flights, the controller may misinterpret the number of cells and therefore allow the voltage to drop too low. For higher cell counts, it’s wise to program the number of cells instead of using “auto” if you tend to do multiple flights on a single charge.

Cutoff mode. Most controllers will allow you to choose whether you want a hard or soft cutoff when they reach minimum voltage levels. A hard cutoff means your motor is going to stop when the voltage is reached. A soft cutoff means the motor will pulse on and off to let you know it’s time to land. Either method allows you to reduce your throttle to idle for a second and then return to normal operation long enough to get it on the ground. Don’t abuse this ability as it is overriding the cutoff and meant to give you power to avoid a dead-stick landing.

Startup mode. This defines how the motor starts when you open the throttle. The choices are generally, “normal,” “soft start,” and “super soft start” or something similar. It’s pretty self-explanatory. Normal is usually the default and fine for most airplanes. If you’re flying a plane with a gearbox, you will want soft to make it easier on the gears and motor when it starts up. If you are flying a helicopter, you will want the softest start mode the unit offers.

Timing. This causes more questions than a paragraph or two can answer. The default for most speed controls is “standard” or “medium” and, unless you really want to get into learning motor theory and optimize for competition, you’re safe leaving this alone. The instructions will give you special notes in case you have a problem with your motor not running smoothly and that’s the best place to go.

PWM switching frequency. Once again, stick with the factory defaults unless there is a problem. This number represents the number of times per second that a pulse is sent to the motor. This may be between 8,000 and 32,000 times per second (see “The PWM Mystery” sidebar).

Operating mode. Most controllers give the option of selecting a pre-programmed set of parameters such as “airplane,” “glider,” or “helicopter.” When you choose one of these operating modes, the speed control will have preset features to optimize that choice. When choosing “helicopter,” many will let you activate a governor mode to help with throttle/collective coordination and use the softest start mode. The “glider” mode usually sets a hard brake, assuming you’re using a folding prop.

CHECK OUT GREG GIMLICK’S COMPLETE FEATURE IN THE 2012 ULTIMATE ELECTRICS SPECIAL ISSUE, ON NEWSSTANDS MARCH 20, 2012 (also available at AirAgeStore.com).

thank you for the info. It cleared up some questions I had as to the meaning of the terms for programming the ESC.

Thanks for the great article. I get a better understanding of an

esc’s operation and settings each time I read one.