If it ain’t a Pitts, it ain’t an airplane!

by BUDD DAVISSON

photos by Norm Feltwell & Budd Davisson

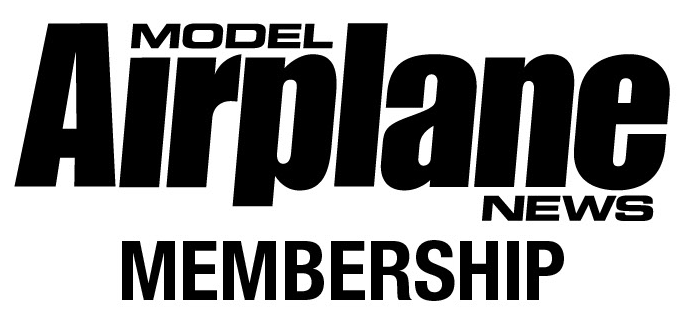

Close your eyes and try to picture this: You are sitting in a much smaller than usual cockpit. The sides of the cockpit come up to your chin and the top of the instrument panel seems to be nearly eye level so you can’t quite see over the nose in level flight! You feel a little like a prairie dog peeking out of a tube-and fabric burrow. The Pitts Special isn’t built for comfort. It’s built to perform as few airplanes in the world can. It is built to inflict the most joyful kind of three dimensional sensations imaginable. In all its variations, it is a vein-busting, G-generating, Oh-my-God machine that stands head and shoulders above just about every airplane ever built. It is, on one hand, totally forgiving and compliant, and yet potentially nasty and willful on the other. It is always a challenge. It challenges you to do better, to be more precise. It also challenges your judgment, since, more than any other airplane I know, it sings a siren song that makes you want to fly lower and judge your talents against that most unforgiving of all judges, the ground.

To put it quite simply, the Pitts Special is the standard by which all other sport aircraft are judged. It’s hard to believe that the original Pitts Special design is as old as it is. Just after World War II a Florida cropduster, soon to become a legend, Curtis Pitts, decided he wanted to build a sport biplane to give him some relaxation away from flying the 450-horse Stearmans he had been using to dust cotton. The final result, a tiny 85-horse biplane with 17-foot wings, was the original seed from which grew a dynasty.

Oddly enough, the little

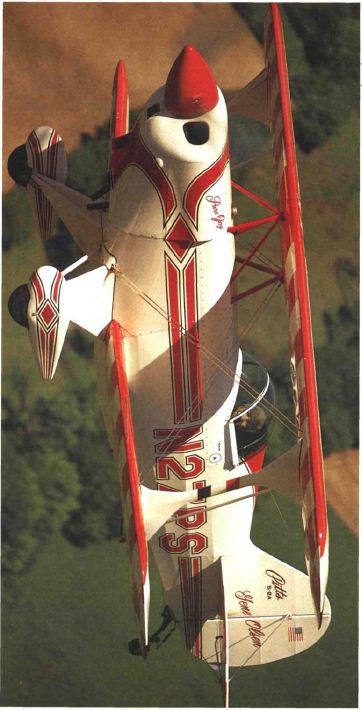

bipe didn’t catch on as quickly as you would think. This was the era of the 450 Stearmans and airshow crowds that loved lots of noise and smoke (they still do). However, one airshow pilot, women’s national champion Betty Skelton, adapted the little airplane to her show work and named it “Li’l Stinker.” For most of the 1950s it was hard to enter a hobby shop of any size without seeing at least one model of the famous “Lil Stinker.”

During that period aerobatics laid around as a very low profile, almost-nonexistent spoil. It wasn’t until the mid-1960s that it began to return to the popularity it had in the 1930s. About the same time world acrobatic contests were begun, and American pilots quickly learned their aging Great Lakes and hulking Stearmans were no match for the nimble little Buckers and Zlins of the Europeans. They turned to the Pitts Special and immediately began hot-rodding the airplane to make it a world class competitor. By the late 1960s, however, world acrobatic contests had begun to score outside maneuvers extremely heavily. So to compete it meant you had to be able to go outside as well as inside. Curtis Pitts, by this time a mini-manufacturer, responded by redesigning the airplane to include wings with symmetrical airfoils and ailerons in both wing panels. This became known as the “round wing” Pitts, now standard.

By the early 1970s aerobatics competition had become, if not big business, at least a high profile sport demanding highly specialized machines that were not always available on the home-built market. Again Curtis responded by building a special, certified single-place machine, the S-1T. This was a 200-horse bird with a fixed-pitch propeller that was designed to do one thing, light it out with the Russians in an acrobatic box. If there is one constant in acrobatic competition, it is that an airplane never has enough power or enough vertical performance. But since the little single-place S-1 Pitts couldn’t possibly hold too much more engine, the obvious move was to put a 260-horse Lycoming on the S-2 airframe and eliminate the front seat. This was done and the result was called the S-2S. Then, of course, a lot of folks decided they would like to share all that performance with someone else and the demand for a second seat came along. This resulted in a certified S-2B. a 260-horse version of the S-2A. So much for the historical nitty-gritty, let’s get down to the important facts of life. In my case, those facts include NI6PS. an S-2A Pitts I’ve owned for nearly thirteen years now. That’s a long time to have a love affair with the same fat lady but I really can’t help myself any more than I could have kept myself from buying an S-2A in the first place. 1 had been assigned to go down to Curtis Pitts’ grass strip in Homestead, Florida, to do a pilot report on 22 Quebec, the prototype S-2 which he called “Big Stinker.” Up to this point 1 had flown my share of acrobatic airplanes, or at least I thought I had. Sitting at the end of Pitts’ short little tree-lined grass strip a thought went through my mind. “This is no Citabria!”

Half-buried in the cockpit I was fully aware that raw performance was its only reason for existence, a fact rammed home as soon as the power came up. At that point, I got my first taste of a true hell-raising airplane. Today, as 1 walk out to the airplane, takeoffs have become a highly anticipated ritual. After strapping in and lighting the coals on that 10-360 Lycoming. I roll out on the runway and consciously judge the tiny triangular visibility that exists at each side of the instrument panel. As in any high-performance airplane, I bring the power up smoothly and gently. You have to remember it’s a big engine and a big prop on a tiny airplane but, if you bring the power up slowly, there’s no problem. The same is true about picking up the tail: I keep it pinned to the ground until the power is all the way in and I’m rolling fairly quickly. the Lycoming are directly under my feet and the harsh, hard-sounding exhaust noise pounds into the cockpit and fills every corner with noise so solid you feel like you can touch it.

At the same time the runway is streaking by so fast and my feet seem connected directly to my eyes. The rudders are extremely sensitive and demand only the tiniest little pitter-patter of a tap dance. With the tail up, I can’t see over the nose as it absolutely rockets straight ahead. My mind tells me I am tangled in the tail of a racehorse and am being dragged behind, but can’t possibly let go. As it starts hippity-hopping on the main gear it gives you the indication that it’s ready to go flying, and gently increasing the back pressure points your nose up. At 95 mph, the best rate of climb speed, you’re going up so steep that you can’t see anything but instrument panel, wings, and wires.

Flying a Pitts is a real exercise in restraint. You don’t do anything harsh or obvious with your hands. In fact, in normal flying the stick never moves as much as half an inch in any direction. But that’s in normal flight and Pitts Specials aren’t made to be flown “normal.” The precision of the Pitts is, of course, legendary. It will start and stop so sharply that you can almost shave on the corners of the maneuvers. Ah, yes, the maneuvers! For all practical purposes, the airplane has no limitations. Designed to a 9G yield and 13G ultimate, it would take a wart hog to yank the controls hard enough to get even 9G. Red line on the air speed indicator is 204 mph which is unattainable in anything except the very steepest of dives. The fuel and oil systems are set up so that the engine really doesn’t care if it’s inverted.

The aerodynamics of the airplane are so well designed that it absolutely doesn’t know whether it’s right-side up or upside down. What’s more, it doesn’t seem to care. One thing people are always surprised to hear is how good a Pitts is at slow speed. The airfoils on the wings are set up so the top one always stalls first whether right-side up or upside down. This means the bottom wing is always flying and one set of ailerons is always working. I can sit there with the stick in my lap, absolutely stalled, and still have enough aileron to roll the airplane over on its back. It’s totally docile in the stall and you can probably fly the approach with the stick in your lap, although your rate of descent would be about the same as a shot put!

Then there is the landing…another part of the Pitts Special legend. The Pitts’ lack of visibility is the primary reason a lot of Pitts pilots use Navy-type, carrier-approach in which the turn from downwind leg is a big 180-degree turn that terminates in the landing flair. The reason for that type of approach is obvious…you always have the runway in sight. Getting lined up in the c

enter of the runway, when you roll out the turn, is critical since you don’t see the runway until it is almost too late to correct. If you hit straight, you’ll find yourself doing a little tap dance on the rudders but, if you hit crooked, all hell breaks loose and you gain a great familiarity with the brakes and rudders all at the same time. Fortunately, the airplane has so much control that you can get it out of any kind of situation on the runway, if you don’t overdo things. In short, you have to stay on it every inch of the way. But that’s part of the challenge of a Pitts Special.

Curtis Pitts and his little airplane were single-handedly responsible for changing the face of world aerobatics. He introduced the true high-performance aerobatic airplane and rewrote the book on how airplanes are supposed to fly. Even Leo Loudenslager credits Curtis with giving him great help in developing the User 200.

The Pitts Special is probably the most “pilot intensive” and demanding airplane to fly in the world, but you won’t find anyone who’s flown one for any length of time who doesn’t love it. So what’s not to love about a machine that lets you defy the laws of gravity and common sense all at one time?

Caption: Airshow pilot and woman’s national champion Betty Skelton adapted the Pitts to her show work and called the “Li’l Stinker,” greatly enhancing the popularity of the little plane.